I read Geoffrey Pullum’s The Truth About English Grammar. It condenses some of his textbook with Rodney Huddleston called A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar, which is itself a condensed version of the 1800 page The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language.

The book has two focuses. The first is a redefinition and recategorization of words. Pullum doesn’t care for the definitions that textbooks traditionally give for the parts of speech at all. (He also doesn’t like the term parts of speech.) Take, for example, adverb. Most grammars say that adverbs can modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. Some also say adverbs can modify entire sentences (as in Thankfully, she wasn’t hurt.) But that’s plainly insufficient. Adverbs can also modify prepositions:

This piano is completely out of tune.

Or determiners (Pullum prefers the term “determinative” to align them with “adjective” and “demonstrative”):

There were hardly any nuts left.

They can even modify nouns:

The news recently that he had died shocked us.

In the above example, it must be modifying the noun. The news is what was recent; the death could have happened at any time. And the sentence has a different meaning than The news that he had died shocked us recently, where recently is modifying the verb phrase shocked us. The noun is all that’s left.

When traditional grammars discuss such cases, they often say that a word is acting as another category of word. In this case, they might say that it’s an adverb acting as an adjective.

That explanation confuses category and function. Recently in the example above is taking a function usually attributed to adjectives. But it does not act (that is, behave) as an adjective at all. It can’t be placed before the noun. *The recently news… is ungrammatical. It can appear in many more places in the sentence than an adjective can. The following examples are all grammatical. They change the meaning of the sentence, but they’re allowed.

Recently, the news that he had died shocked us. |

The news that he had recently died shocked us. |

The news that he had died recently shocked us. |

The news that he had died shocked us recently. |

Not a single one of these variants would be grammatical with the adjective recent.

As another example, Christmas is a noun, and it doesn’t cease to be one when it modifies another noun, as in Christmas tree. Like the adverb example, it isn’t a noun “acting as an adjective.” It behaves nothing like an adjective, except that it can be preposed before a noun to modify it. It can’t be placed after the copula as adjectives can: %1This tree is Christmas. Nor does it share basically any of the other properties of adjectives, like the ability to be modified by adverbs. (*This is a more Christmas tree than that one.) It is a noun acting as a noun modifier, not as an adjective.

Pullum’s also not happy with the classification of some words. Probably the biggest change that he wants is to expand the class of prepositions. In what are often called phrasal verbs, there are postpositive prepositions, as in My horse fell down. In the past these have been classified as adverbs because they modify the verb. But this is the same error as above. Both My horse fell immediately and My horse immediately fell are grammatical, but *My horse down fell is not. Down does not become an adverb when modifying verbs. It makes more sense to say that not all prepositions require an object, the same way that many verbs have both transitive and intransitive uses.

The book’s second focus is a good discussion of what Language Log might call prescriptivist poppycock. There’s a chapter dedicated to passive verb clauses. (He doesn’t like the term passive voice). There’s another chapter about relative clauses. (I discussed them in the last post.) With so many topics about English to discuss, why choose those two? As far as I can tell, it’s because he’s particularly annoyed by the writing advice denigrating the passive voice, or using which to head restrictive relative clauses. I am too, so this is all right up my alley. These chapters are followed by a longer chapter about general mythical grammar errors. It seems to contain the leftovers that, unlike passive and restrictive clauses, didn’t warrant chapter-length discussions.

Even fairly prescriptivist grammar and usage books are opening up to the idea of singular they being acceptable. (It has been grammatical for many centuries, but people are finally accepting that fact.) In the past, they usually recommended using he as a substitute. Pullum points out that, even among people who choose that word in sentences like Every schoolchild knows he should learn how to touch type, they wouldn’t ordinarily say %Did one of your parents injure himself2 or ??3If your brother or sister wants to come, we can invite him.

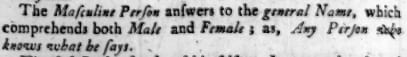

Pullum says that the “he” rule was originally promoted by Ann Fisher in the 1700s. In a moderately negative review of the book, The Guardian points to an example from 1549 which says, “an instruction to be learned of every child, before he be brought to be confirmed of the Bishop,” to prove that the rule is natural English and wasn’t invented by Ann Fisher. Holy misreading, Batman! Pullum didn’t say that, before Fisher, no educated writer ever used he as the solution to the gender-unknown singular referent problem; he said that the idea that he is the correct solution to the problem was originally promoted by Fisher. As in, she wrote the earliest known explicit instruction to use he in all cases:

The Masculine Person answers to the general Name, which comprehends both Male and Female ; as, “Any Person who knows what he says.”

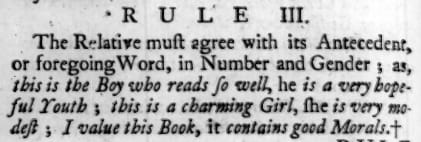

This is tucked in as a footnote under a section which says:

Rule III: The Relative must agree with its Antecedent, or foregoing Word, in Number and Gender ; as, “this is the Boy who reads so well, he is a very hopeful Youth” ; “this is a charming Girl, she is very modest” ; “I value this Book, it contains good Morals.”

Pullum’s point is that he cannot be used as a fully general solution to the problem. English has never really allowed that. Singular they, on the other hand, can.

(By the way, regarding that same review, some of its author’s other complaints are due to similar misreadings. For example, the author uses So silly! as a counterexample to Pullum’s claim that exclamatory clauses begin with what or how. But so silly! is not a clause at all; it’s an adjective phrase. And Pullum denies that clauses ending in exclamation points are exclamatory clauses. He defines clause type based on grammatical features of the clause, not on the punctuation at the end. So even a genuine clause like That’s so silly! would still be declarative. Using So silly! as counterevidence is, uh, very silly.)

I’ll end with a fun factoid I’d never thought of before: Some nouns are neither mass nor count nouns. Midst, for example, must be a noun because it only occurs where other nouns can occur. (Consider in the midst of the turmoil vs. in the heat of the moment. Or a traitor in our ranks vs. a traitor in our midst.) But it’s not a count noun: there’s no such word as midsts. And it’s not a mass noun: it can’t be modified as *more midst. It’s neither, somehow. English is ridiculous.

1 A percent sign indicates that the following sentence is semantically odd. It’s not ungrammatical per se, but it’s not something that would ever be said by a native speaker except in extremely specific circumstances. For example, The hot dog ate the man is grammatical, but only makes sense in a story about a giant man-eating hot dog. In my example, the tree could be Christmas in some bizarre fantasy world where holidays are being turned into trees, but the sentence cannot have the meaning This is a tree of the Christmas variety or This tree is Christmassy.

2 Technically fine if all of someone’s parents are men, so I’ve marked with a % instead of * or ??.

3 Pullum uses ?? for questionable grammaticality, as I will here. I can’t say this usage never occurs, but it sounds ridiculous to me.